Before we start: Overview of the classes and interfaces

When we talk about iText's basic building blocks, we refer to all classes that implement the IElement interface. iText is originally written in Java, then ported to C#. Because of our experience with both programming languages, we've adopted the convenient habit - typical for C# developers - to start every name of an interface with the letter I.

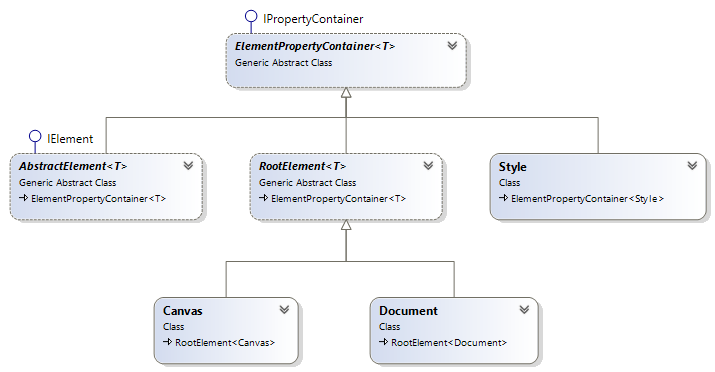

Figure 0.1 shows an overview of the relationship between IElement and some other interfaces.

Figure 0.1: Overview of the interfaces

At the top of the hierarchy, we find the IPropertyContainer interface. This interface defines methods to set, get, and delete properties. This interfaces has two direct subinterfaces: IElement and IRenderer. The IElement interface will be implemented by objects such as Text, Paragraph and Table. These are the objects that we'll add to a document, either directly or indirectly. The IRenderer interface will be implemented by objects such as TextRenderer, ParagraphRenderer and TableRenderer. These renderers are used internally by iText, but we can subclass them if we want to tweak the way an object is rendered.

The IElement interface has two subinterfaces of its own. The ILeafElement interface will be implemented by building blocks that can't contain any other elements. For instance: you can add a Text or an Image element to a Paragraph object, but you can't add any object to a Text or an Image element. Text and Image implement the ILeafElement interface to reflect this. Finally, there's the LargeElement interface that allows you to render an object before you've finished adding all the content. It's implemented by the Table class, which means that you add a table to a document before you've completed adding all the Cell objects. By doing so, you can reduce the memory use: all the table content that can be rendered before the content of the table is completed, can be flushed from memory.

The IPropertyContainer interface is implemented by the abstract ElementPropertyContainer class. This class has three subclasses; see figure 0.2.

Figure 0.2: Implementations of the IPropertyContainer interface

The Style class is a container for all kinds of style attributes such as margins, paddings and rotation. It inherits style values such as widths, heights, colors, borders and alignments from the abstract ElementPropertyContainer class.

The RootElement class defines methods to add content, using either an add() method or a showTextAligned() method. The Document object will add this content to a page. The Canvas object doesn't know the concept of a page. It acts as a bridge between the high-level layout API and the low-level kernel API.

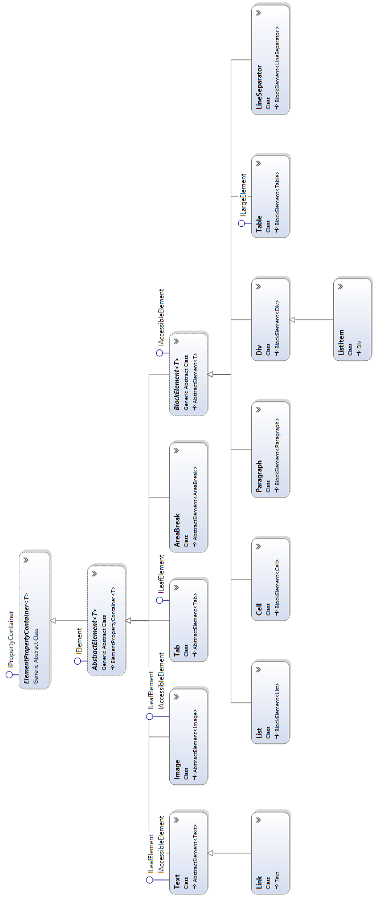

Figure 0.3 gives us an overview of the AbstractElement implementations.

Figure 0.3: Implementations of the IElement interface

All classes derived from the AbstractElement class implement the IElement interface. Text, Image, Tab and Link also implement the ILeafElement interface. The ILargeElement interface is only implemented by the Table class. The basic building blocks make it very easy for you to create tagged PDF.

Tagged PDF is a requirement for PDF/A level A, a standard for long-term preservation of documents, and for PDF/UA, an accessibility standard. A properly tagged PDF includes semantic information about all the relevant content.

An ordinary PDF can show a human reader content that is organized as a table. This table is rendered using a bunch of text snippets and lines. To a machine, the table isn't more than that: text positioned at arbitrary places, lines drawn at arbitrary places. A seeing person can detect rows and columns and understand which rows are actually header or footer rows and which rows are body rows. There is no simple way for a machine to do this. When a machine detects a text snippet, it doesn't know if that text snippet is part of a paragraph, part of a title, part of a cell, or part of something else. When a PDF is tagged, it contains a structure tree that allows a machine to understand the structure of the content. Some text will be marked as part of a cell in a header row, other text will be marked as the caption of the table. All real content will be tagged. Other content, such as lines between rows and columns, running headers, page numbers, will be marked as an artifact.

The semantic meaning of all elements that implement the IAccessibleElement interface will be added to the resulting PDF if we define a PdfDocument as a tagged PDF using the setTagged() method. In that case, iText will create a structure tree so that a Table is properly tagged as a table, a List properly tagged as a list, and so on. This is true for the Text, Link, Image, Paragraph, Div, List, ListItem, Table, Cell, and LineSeparator objects. The Tab or the AreaBreak object don't implement the IAccessibleElement interface because they objects don't have any real content. The whitespace they create doesn't have any semantic meaning.

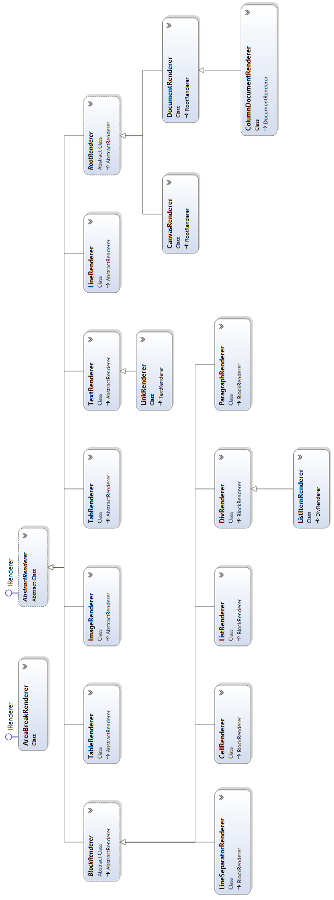

In this tutorial, we won't create tagged PDF; iText will just render the content to the document using the appropriate IRenderer implementation. Figure 0.4 shows an overview of the IRenderer implementations.

Figure 0.4: Implementations of the IRenderer interface

When you compare figure 0.4 with 0.3, you'll discover that each AbstractElement and each RootElement has its corresponding renderer. We won't discuss figure 0.4 in much detail. The concept of renderers will become clear the moment we start making some examples.